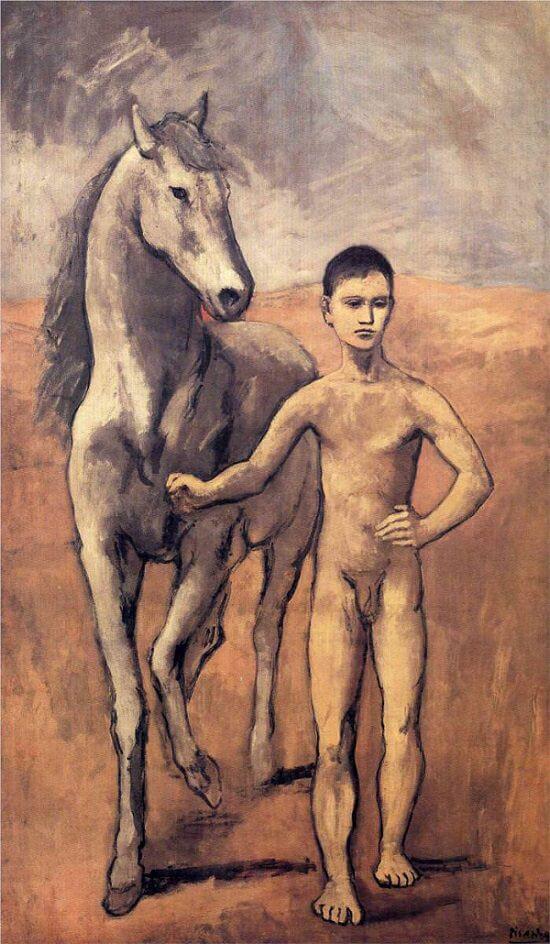

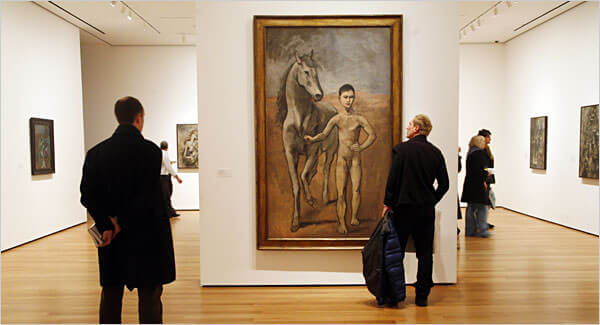

Boy Leading a Horse, 1906 by Pablo Picasso

|

| Courtesy of www.picassofamily.org |

Boy Leading a Horse is yet another masterpiece critics praise without trying to explain. Either they believe it has no meaning or that explaining it is impossible. That is no reason not to try. The more difficult an image is to interpret, the more you will experience aesthetic satisfaction when you do start to understand it. Richardson searched for Picasso's sources but gave up, calling the picture "derivative." The painting, though, must mean something; all masterpieces do and it is our job to figure them out. Sources, as always, are key. The two figures - horse and boy - first appeared as a sketch for a much larger masterpiece that was never finished.

No expert seems to have noticed that the horse in the picture under discussion is derived from Mantegna's Parnassus in the Louvre. Parnassus was the mythic home of the arts. Hermes and Pegasus, the winged horse, are in the right foreground of Mantegna's image (far left) rather like a signature. This discovery leads to another homonym. Pegasus in Spanish is Pegaso. The reason why Picasso changed his last name from Ruiz to Picasso is now much clearer as revealed in the analysis of another painting, Picasso's Parade.

|

Boy Leading a Horse also indicates that Picasso had discovered a contemporary hero to complement his antique sources: Paul Cezanne. The heroic, but clumsy and rather brutal The Bather, which was in Vollard's stock, looks as if it was the model. When seen in proximity the similarities in handling as well as composition are striking, and Picasso's frank appeal to the authority of the Antique is thrown into relief by the more naive appearance of The Bather. Since the turn of the century Cezanne's paintings had been interpreted by disciples such as Denis and Emile Bernard as a highly original continuation of the French classical tradition. The revelation of his late Bather paintings and Aix landscapes in the sequence of exhibitions organized from 1904 onwards, coupled with the publication of aphoristic statements expressing his veneration for the great tradition and his personal commitment to an equal balance between 'the eye and the mind', made Cezanne seem the perfect 'primitif classique' of modern painting, the perfect antidote to Bouguereau. To Denis in 190c his style was admirably 'severe' and 'chaste', and even his watercolours - 'as carefully structured as oil paintings' - seemed like 'ancient pottery'. This kind of commentary justified Picasso's imaginative and seamless fusion of references to early Greek sculpture and Cezanne's male bather in Boy Leading a Horse