Guernica, 1937 by Pablo Picasso

|

| Courtesy of www.picassofamily.org |

Probably Picasso's most famous work, Guernica is certainly his most powerful political statement, painted as an immediate reaction to the Nazi's devastating casual bombing practice on the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War.

Guernica shows the tragedies of war and the suffering it inflicts upon individuals, particularly innocent civilians. This work has gained a monumental status, becoming a perpetual reminder of the tragedies of war, an anti-war symbol, and an embodiment of peace. On completion Guernica was displayed around the world in a brief tour, becoming famous and widely acclaimed. This tour helped bring the Spanish Civil War to the world's attention.

This work is seen as an amalgamation of pastoral and epic styles. The discarding of color intensifies the drama, producing a reportage quality as in a photographic record. Guernica is blue, black and white, 3.5 meters (11 ft) tall and 7.8 meters (25.6 ft) wide, a mural-size canvas painted in oil. This painting can be seen in the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid.

Interpretations of Guernica vary widely and contradict one another. This extends, for example, to the mural's two dominant elements: the bull and the horse. Art historian Patricia Failing said, "The bull and the horse are important characters in Spanish culture. Picasso himself certainly used these characters to play many different roles over time. This has made the task of interpreting the specific meaning of the bull and the horse very tough. Their relationship is a kind of ballet that was conceived in a variety of ways throughout Picasso's career."

Some critics warn against trusting the political message in Guernica. For instance, the rampaging bull, a major motif of destruction here, has previously figured, whether as a bull or Minotaur, as Picasso's ego. However, in this instance the bull probably represents the onslaught of Fascism. Picasso said it meant brutality and darkness, presumably reminiscent of his prophetic. He also stated that the horse represented the people of Guernica.

|

| Museum Photo of Gurnica |

Historical Context of the Masterpiece

Guernica is a town in the province of Biscay in Basque Country. During the Spanish Civil War, it was regarded as the northern bastion of the Republican resistance movement and the epicenter of Basque culture, adding to its significance as a target.

The Republican forces were made up of assorted factions (Communists, Socialists, Anarchists, to name a few) with wildly differing approaches to government and eventual aims, but a common opposition to the Nationalists. The Nationalists, led by General Francisco Franco, were also factionalized but to a lesser extent. They sought a return to the golden days of Spain, based on law, order, and traditional Catholic family values.

At about 16:30 on Monday, 26 April 1937, warplanes of the German Condor Legion, commanded by Colonel Wolfram von Richthofen, bombed Guernica for about two hours. Germany, at this time led by Hitler, had lent material support to the Nationalists and were using the war as an opportunity to test out new weapons and tactics. Later, intense aerial bombardment became a crucial preliminary step in the Blitzkrieg tactic.

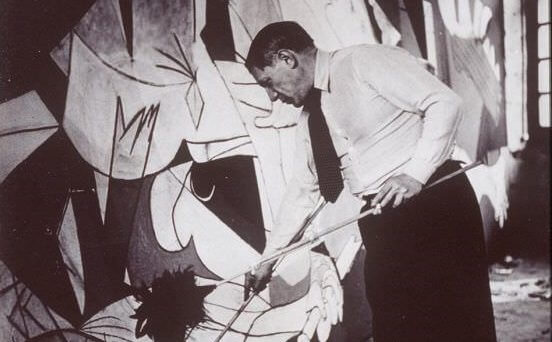

|

| Photo of Picasso working on Gurnica. |

Guernica is an icon of modern art, the Mona Lisa for our time. As Leonardo da Vinci evoked a Renaissance ideal of serenity and self-control, Guernica should be seen as Picasso's comment on what art can actually contribute towards the self-assertion that liberates every human being and protects the individual against overwhelming forces such as political crime, war, and death.

10 Facts of Guernica

1. Guernica, Picasso's most important political painting, has remained relevant as a work of art and as a symbol of protest, and it kept the memory of the Basque town's nightmare alive. While Picasso was living in Nazi-occupied Paris

during World War II, one German officer allegedly asked him, upon seeing a photo of Guernica in his apartment, "Did you do that?" Picasso responded, "No, you did."

2. Guernica was a commissioned painting. After the bombing of Guernica, Picasso was made aware of what had gone on in his country of origin. At the time, he was working on a mural for the Paris Exhibition to be held in the

summer of 1937, commissioned by the Spanish Republican government. He deserted his original idea and on 1 May 1937, began on Guernica. This captivated his imagination unlike his previous idea, on which he had been working

somewhat dispassionately, for a couple of months. It is interesting to note, however, that at its unveiling at the Paris Exhibition that summer, it garnered little attention. It would later attain its power as such a potent symbol of the destruction

of war on innocent lives.

3. Perhaps because Picasso learned about the Guernica bombing by reading an article in newspaper, the suggestion of torn newsprint appears in the painting. It doubles as the horse's chain mail.

4. Picasso's patriotism and sense of justice outweighed physical location. He had not been to Spain, the country of his birth, for several years when the Nazis bombed the Spanish town of Guernica in 1937. He was living in Paris at the time,

and never returned to his birthplace to live. Nevertheless, the attack, which killed mainly women and children, shook the artist to the core.

5. In 1974, an antiwar activist and artist, Tony Shafrazi, would deface the mural with red spray paint as a protest statement. It was on display at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art at the time. Curators immediately cleaned the

painting, and Shafrazi went to jail, charged with criminal mischief.

6. Picasso was adamant that Guernica remains at the Met until Spain re-established a democratic republic. It would not be until 1981, after both the artist's and Franco's deaths,

that Spanish negotiators were finally able to bring the mural home.

7. During his creation of "Guernica," Picasso allowed a photographer to chronicle its progress. Historians believe that the resulting black and white photos inspired the artist to revise his earlier colored versions of the artwork to a starker,

more impactful palette.

8. Not only did the artist use lack of color to express the starkness of the aftermath of the bombing, he also specially ordered house paint that had a minimum amount of gloss. The matte finish, in addition to the shades of grey, white and

blue-black, set an outspoken yet unadorned tone for the artwork.

9. The mural contains some hidden images. One of them is a skull, which is superimposed over the horse's body. Another is a bull formed from the horse's bent leg. Three daggers replace tongues in the mouths of the horse, the bull and

the screaming woman.

10. Two of the artist's signature images, the Minotaur and the Harlequin, figure in Guernica. The Minotaur, which symbolizes irrational

power, dominates the left side of the work. The harlequin, a partially hidden component just off-center to the left, cries a diamond-shaped tear. The harlequin traditionally symbolizes duality. In the iconography of Picasso's art, it is a mystical symbol with power over life and death. Perhaps the artist inserted the harlequin to counterbalance

the deaths he depicted in the mural.