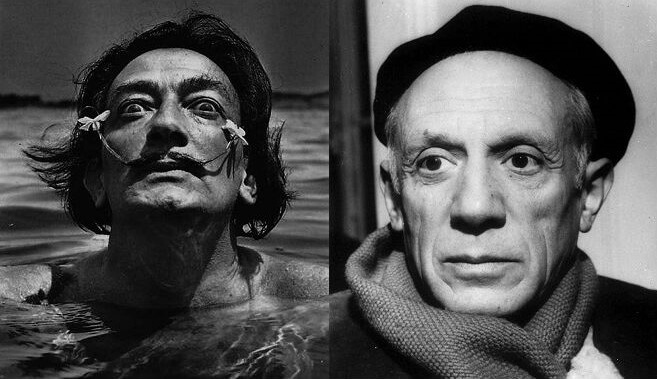

Picasso and Dali

Salvador Dali and Pablo Picasso were the most famous artists of their time, and only Jackson Pollock might

compete with them as the most influential on the art of the 21st century.

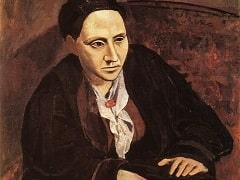

Although born more than 20 years apart (Picasso in 1881, Salvador Dali in 1904), both artists were shaped by the cultural heritage of their native Spain and propelled into modern art by the

intellectual vitality of Barcelona in the 1890s and first decades of the 20th century. Dalí's admiration for the older artist was boundless. When he first traveled to Paris in 1926, Dalí paid homage to Picasso by telling the

already world-renowned master that he had come to meet Picasso before even visiting the Louvre. In following decades, Dalí and his wife, Gala, deluged Picasso with about 100 letters and postcards currying favor (Picasso's

side of the correspondence is unknown). In 1934, Picasso demonstrated his respect for Dalí by paying Dalí's passage to New York for his first exhibition in the U.S. Some of these documents and other fascinating photographs,

magazines, postcards and correspondence are placed in vitrines throughout the galleries.

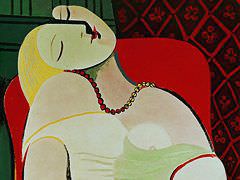

Dalí's lifelong admiration was barbed with competition. Twenty-one years after meeting Picasso, Dalí painted Portrait of Pablo Picasso in the Twenty-first Century,

a masterpiece of Dalí's mature art that hangs at the end of the exhibition and sums up their problematic relationship. The painting is a direct assault on Picasso's reputation as well as the permanence of artistic stature.

Dalí used his remarkable hyper-realism to create a deeply contradictory portrait. Mocking Picasso's prestige by showing him as an antique bust covered in melting flesh, Dalí nonetheless evoked his genius by showing liquid metal

flowing through Picasso's head to shape an attenuated spoon, which encloses one of Picasso's signature and most polymorphous subjects - the guitar.

The mutual rivalry and admiration of Dalí and Picasso spanned more than four decades, ending only with Picasso's death in 1973 (Dalí died in 1989). It began about 1930 with an exchange of tremendous creativity under the sign

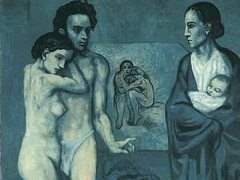

of Surrealism, the movement of visual art and literature founded by André Breton, with support of Freud Theories to explore the profoundest levels of the unconscious and the irrational.

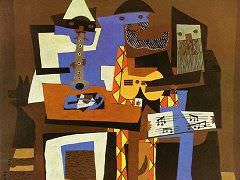

Dalí realized that Cubism, the movement founded by Picasso and Braque in the first decade of the 20th century, contained a structure for picturing states of mind rather than simply

physical appearance. The multiple images of a woman's face that Cubists used to create an impression of a three-dimensional figure on the flat field of a canvas inspired Dalí to turn those images into multiple identities of

an individual or even hallucinatory shifts of matter - a human face might become a donkey's rear end or a rock-strewn beach.

Dalí's exploration of painterly magic matched Picasso's own transformation of Cubism's rigor into polymorphic human figures. In the exhibition, the pairing of Picasso's "The Painter" (1930), a rendering of bodies as boneless

tangles of undulating limbs, with Dalí's "Female Nude" (1928) pinpoints a moment of mutual inspiration between these two artists of different generations and standing in the art world. While Dalí's "Female Nude" draws on

Picasso's massive alteration of human proportions in works of the late '20s, Dalí's Surrealism paintings, illustrated by his masterpiece Persistence of Memory,

both pushes the deviations to a further extreme and couples them with exceptionally realistic details that make the whole creature almost believable. The fecundity and mutual stimulation of this counterpoint no doubt caused

Picasso to deepen his admiration for Dalí.

Yet this comparison also highlights a fundamental difference in the two artists' approaches to painting. No matter how fantastic the imagery, Picasso always rooted his art in an awareness of the difference between an image

and the physical reality of a painting, a profound issue of process he inherited from his artistic father, Paul Cézanne. As an artist of the next generation, Dalí easily dismissed Cézanne's

anxiety. He wholeheartedly accepted painting as an art of pure illusion. Only the seeming reality of his hallucinatory visions mattered to Dalí.

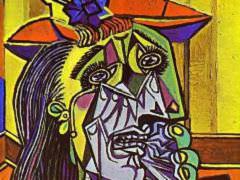

The dialogue extended through the two artists' tortured responses to the devastation of their homeland during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39). While Picasso is best known for "Guernica" (1937), Dalí reacted more quickly to

the threat with his Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (1935). One of the highlights of the exhibition is Dalí's exquisite, large-scale study

of the composition, which shows with disconcerting elegance two bodies struggling to tear each other apart. Picasso's sketches for "Guernica" demonstrate how closely these two artists realized their visions of Spain's peril.

The Civil War also marked the divergence of their careers. When Dalí learned that Picasso had been selected as the artist to paint the primary mural of the Spanish Pavilion of the 1937 World's Fair in Paris, Dalí raged against

him and claimed "Picasso was a great Reactionary." After Gen. Francisco Franco's victory over the Republican government, Dalí cultivated the dictatorship and became a favored artist of the regime. Picasso remained adamantly

opposed to the dictatorship and specified that "Guernica" would never enter Spain until democracy was restored. Moreover, Dalí spent long periods away from Europe. He lived in New York from 1940 to 1948 and enjoyed frequent

residencies in the U.S. over the following decades. During the Cold War, he expanded the scope of this anticommunism, while Picasso remained a Communist from the end of the World War II until his death.

This was the period of Dalí's portrait of Picasso, and it also marked Dalí's increasing self-promotion on a scale commensurate with America's postwar boom. Dalí had already appeared on the cover of Time in 1936, and soon his

columns for the Hearst newspapers as well as outlandish, staged photographs were blanketing the media. After a decade of political activity through the Communist Party, Picasso substantially withdrew from the public arena by

the mid-'50s, even though trusted photographers kept his image in the news (often in shots that shared the goofiness of Dalí's personas).

Toward the end of Picasso's life, the two artists came back in dialogue. The focus was an intermediary - Diego Velazquez, the 17th-century Spanish painter both Dalí and Picasso

admired above all others. Secluded in his villa in the south of France in 1957, Picasso completed an extensive series of paintings that pitted himself against Velázquez's masterpiece, "Las Meninas." The exhibition is privileged

to include one of these large canvases as well as a smaller, finely worked study of the Infanta Margarita María, the main character of "Las Meninas." Presumably aware of Picasso's feat, Dalí painted his own meditation on his

predecessor's achievement, "Velázquez Painting the Infanta Margarita with the Lights and Shadows of her own Glory," an image that follows the title by showing Velázquez at work in the darkened halls of the palace as the

Infanta emerges from the shadows in a pyrotechnic display worthy of the Fourth of July.

If Salvador Dalí's paintings suggest a continuing duel with Picasso, Dalí nonetheless remained one of Picasso's greatest admirers - even long after Picasso seems to

have dropped his side of the exchange.